Posted on: March 22, 2017

Source: San Francisco Chronicle

Posted by | March 22, 2017

Photo: Paul Chinn, The Chronicle

If you know someone who has just moved into the old college building that’s been converted to affordable housing at Laguna and Hermann streets, here’s my tip: Wangle an invitation to stop by.

The curb appeal alone is impressive, with rich stucco and clay tile roofs from when Spanish Revival was all the rage. It’s a shot of Santa Barbara a stone’s throw from Market Street, the scholarly tone enhanced by a big-eyed owl carved into one thick buttress.

But the deepest revelations are inside, down shadowy hallways wide enough to hold the long-gone rush of students spilling from classrooms. This is a rare historic restoration where the aura of history remains, layer upon layer upon layer — including layers that bear the scars of past mistakes.

“You get this sequence of history that plays out, and each piece adds to the experience,” said Fred Pollack of Van Meter Williams Pollack, the architecture firm that recast Richardson Hall for nonprofit developers Mercy Housing and Openhouse. “That’s one of the pleasures of working on buildings like this. It’s a puzzle every time.”

The complexity of the puzzle can be seen in something as simple as the two entrances from the street, both of which lead to space constructed between 1924 and 1930.

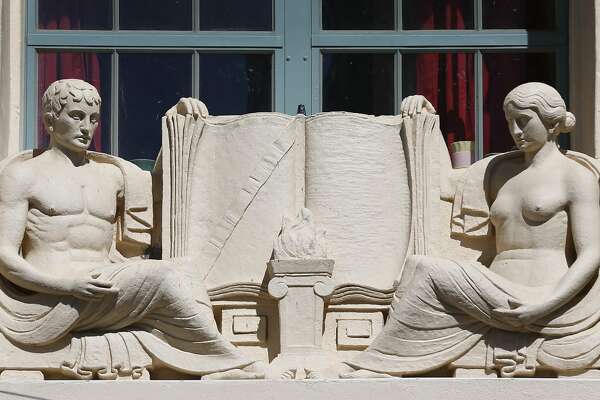

The entrance on Hermann is where students ascended through a portal topped by sculpted classical figures holding the proverbial Book of Knowledge. Inside was San Francisco State Teachers College, which became San Francisco State College in 1935 and now is San Francisco State University. When the college moved to the shores of Lake Merced in 1957 the block bounded by Laguna, Hermann, Buchanan and Haight streets became the University of California Extension.

These days, the doors inside the portal are locked on the outside, since they flunk all accessibility requirements. The front door is around the corner at 55 Laguna, wide and glassy, opening to a foyer that offers the choice of stairs or an elevator.

Upstairs, the 40 apartments line corridors with layered histories all their own.

They’re wide and tall, with sturdy plaster surfaces and the occasional barrel-vaulted ceiling to mix things up. At one turn, the walls are adorned with murals by Jack Moxie that the federal government commissioned in 1935 as part of its Works Progress Administration effort to fight the Great Depression.

The story doesn’t end there.

In the 1950s, college officials decided to cut a pair of new service openings into Richardson’s auditorium — through the murals. And then cover them with paint, same as with the other dozen or so murals by Moxie sprinkled through the building. Simple as that. In a decade determined to remake all aspects of American society, why show any respect to details that might be in the way of progress?

By the time that Pollack’s firm was working with preservation architects Page & Turnbull to adapt Richardson Hall for housing, attitudes had changed. Testing determined that remnants of Moxie’s angelic but somber students were still beneath the subsequent coats of industrial paint, so restoration specialists got to work.

“We looked into re-creating the portions of the murals that were destroyed, in a lighter color,” Pollack said. “But work like that is very expensive.” Personally, I like the fragmentary restoration. It forces questions on the viewer. There’s no pretense that we knew best all along. The makeover of Richardson Hall involves subtractive work outside as well, keyed to changing notions of how the city should work.

That entrance on Laguna Street is part of a ground-level sequence that includes a cafe space at the corner and the new Bob Ross LGBT Senior Center. Before the redevelopment of the block, none of those spaces existed — the sidewalk was flanked by a bulky retaining wall to hold up the steep hillside and the parking lot on top.

But now the parking lot has been replaced by a market-rate development of six-story buildings (Woods Hall, another remnant of S.F. State days, has also been restored nicely along Haight Street by BAR Architects). Laguna Street is seen as the front of the transformed block, rather than the backside of the hill.

The developers and Pollack’s firm worked with city planners and the Historic Preservation Commission to determine precisely how much of the wall could be removed. The issue was historic integrity, not the structural kind: Richardson Hall is a landmark. The grim face to Laguna was one of its original features.

Bas-relief sculpture is preserved on the exterior of Richardson Hall on Laguna Street in San Francisco, Calif. on Tuesday, March 21, 2017. At one time part of the San Francisco State Teacher’s College, Richardson has been renovated as LGBT-friendly affordable housing for seniors. Photo: Paul Chinn, The Chronicle

“We didn’t want a blank wall,” Pollack said. “Planners wanted it to continue to feel like a wall, not a series of columns.”

The final layer is hinted at in the Bob Ross center, which is operated by co-developer Openhouse, a nonprofit focused on the gay community.

In community hearings involving the restoration of Richardson Hall, there was a push to target the affordable housing for lower-income Castro residents with few options as they aged. Fast-forward to 2017, and the marketing effort for this “LGBT-friendly” complex was successful enough that 70 percent of the residents who moved in over the winter identify themselves as gay.

In its first life, Richardson Hall served aspiring students. Now it’s a place for older people to wind down their lives. Yet the scholarly owl still stands guard above the corner, and the quiet halls still tell their tales.

Posted in: News